Topic List

General Comments

A Facebook reader asked: Who qualifies as a traditional oil painter? Do the Impressionists qualify? What about WJM Turner?

Virgil’s answers:

If I’m asked to specify a definite demarcation, it would be the point at which the intent to create images that read realistically failed miserably or was consciously eschewed. So the Impressionists could arguably fit in adequately with “traditional,” but not the Post-Impressionists except for perhaps the best things Van Gogh did, and not the fauves, cubists, abstract expressionists, and other so-called “modern” art movements. The best of the Surrealists deserve respect because the command of realist technique is required to make it work. Photorealism I consider a grey area, but outside of my interest and my intended focus for this group.

A tradition is something that was practiced for a significant period of time, presumably more than one generation, so with that understood, it becomes a question of which tradition we’re referring to. The tradition of using oil paints to create images intended to read realistically is the tradition this group is concerned with. So that would include Turner, Millet, Sargent, and the Impressionists, all of whom were trying to create realistic illusions with oil paints.

Rembrandt

Virgil discusses Rembrandt at length in Chapter 6, “Techniques of Painting in Oils” and in particular the subtopic “Innovations of Rembrandt”, p 92-99.

“As I wrote in my book, Rembrandt was not limited to a single approach. His usual method, however, was to begin in monochrome brown to establish the basic design, with lead white where needed for heightening lights. Color would be brought in after the brown monochrome, and in color, he could either work alla prima or in stages involving impasto underpainting, opaquely modeled passages, and finishing glazes for certain special effects to enhance the illusion of three-dimensional depth.”

A Facebook reader asks: “How did Rembrandt start and develop a painting?”

Virgil’s reply: “The best indication, gleaned from unfinished paintings, is that Rembrandt generally began in brown monochrome to establish the design of the painting and the patterns of light and dark, then worked in color over that, opaquely in the areas of light, and in varying degrees of opacity, transparency, and translucency in the shadows and other darks, and then in the final stage applied refining touches including glazes and scumbles as he saw fit, to create different optical effects. He also created certain special effects by executing highly textured underpaintings of white or yellow in certain areas, and then glazing over them when dry, and wiping the glazes off the high spots while leaving them in the depressions. In some small works, he appears to have painted directly, alla prima, either from the start or over a brown monochrome underpainting.”

Recommended Reading:

- “Rembrandt – The Painter at Work”, by Ernst van de Wetering.

- “Rembrandt – The Artist Thinking”, by Ernst van de Wetering.

- “Art in the Making – Rembrandt” by conservation scientists at the National Gallery in London.

Additional Resources:

A YouTube tutorial on Rembrandt’s working methods. (English subtitles)

A Facebook reader asks how Rembrandt might have approached this character study called “The Laughing Man”. Was it done alla prima?

Virgil’s reply: “Rembrandt’s general procedure was to begin in monochrome browns heightened with white, then to develop in color beyond that, sometimes in stages, and perhaps sometimes alla prima. I suspect this one was done with the collar and garment on a mannequin, and then the head added afterwards in one or two sessions, judging by the way it looks. In the first session for the head he probably worked in his usual brown monotone, and then either proceeded immediately to color in that same sitting, and finished it alla prima, or let the brown dry and then painted in color in a subsequent session. Rembrandt was perfectly capable of painting alla prima as well as in multiple laters, obviously.”

“… I surmise he used a mannequin for the clothing and arms, and then painted the head in a live sitting or sittings with the subject, whose own proportions were perhaps different from those of the mannequin, thus accounting for the abbreviated shoulders and/or too-short arms.”

Alla prima is often done on a toned canvas or panel. If the tone works as it is, and thus is left bare in places, it’s still alla prima. If a previous painting is painted over entirely in a subsequent session, some people might call that alla prima, but I wouldn’t, because oil paints are not fully opaque, so the influence of the painting being painted over would probably affect the end appearance. (Side notes: Alla prima is painting wet-into-wet; if there is an underpainting, the technique used isn’t alla prima.)

On the subject of glazing:

An example of Sgraffito, a technique that involves scratching through a layer of still-wet paint to reveal what’s underneath, whether this is a dried layer of paint or the white ground on the support. Any object that will scratch a line into the paint can be used for sgraffito.

On the subject of backgrounds:

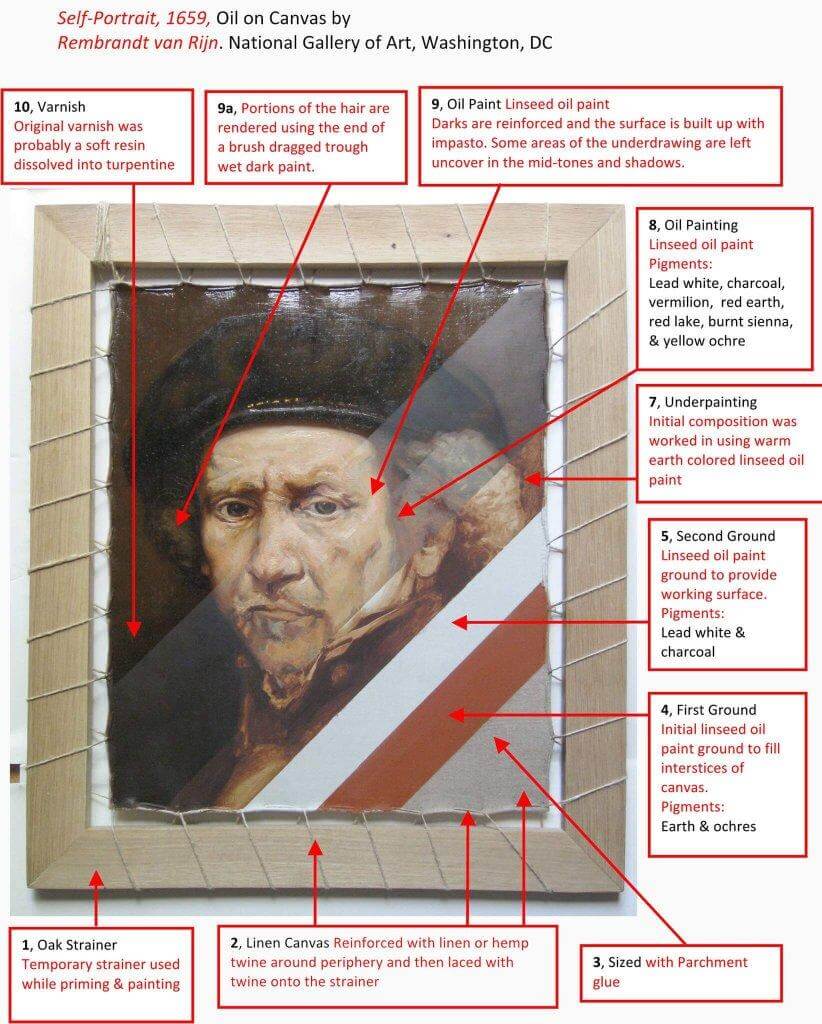

This illustration below is “Rembrandt Reconstruction, Self Portrait 1659”, from the Conservators at the Univ. of Delaware (MITRA).