Table of Contents

Cadmium Red

Pigment Number: PR108

Virgil’s Assessment:

Virgil’s Rublev palette includes: Cadmium Red Light, Cadmium Red Medium.

A single pigment is often used to produce several different colors. PR 108 can cover a wide range of red shades, and the name of the colour gives an indication of its exact shade. Cadmium Red Light, for example, will lean more towards orange while Cadmium Red Deep is more of a maroon shade.

Re: Toxicity: If your objection to cadmium reds is based on the belief that they’re toxic, it might interest you to know that the cadmium compounds in these oil paints are not sufficiently bioavailable to present a significant health hazard. This was the upshot of ASTM’s argument in convincing US Congress not to ban cadmium paints back around 1990. It was demonstrated that they are not water-soluble, so cannot poison groundwater, and they aren’t a health hazard because our bodies can’t absorb them. They aren’t pure cadmium. It’s still prudent to not be sloppy or careless in handling oil paints, of course.

Technical Links:

The Color of Art Pigment Database: Red Pigment PR108

Pigment Through the Ages: Cadmium Red. “It has very high hiding power and good permanence. A cadmium red was available as a commercial product from 1919. The pigment was used sparingly due to the scarcity of cadmium metal and therefore because it was more expensive.”

Pyrolle Red

Pigment Number: PR254, PR255

Pyrolle reds are good substitutes for cadmium.

Pyrrole Red PR 254 has very high lightfastness but it isn’t fully transparent. They’re less opaque than cadmium reds, but not as transparent as madder lake or alizarin crimson, so I wouldn’t call them fully transparent. Adding a small amount of Oleogel or Oleorezgel would make them suitably transparent, however.

Technical Links:

The Winsor & Newton website has an article on the history of Pyrolle Red and its connection to Ferrari race cars.

Rose Madder

Pigment Number: NR9

Another name for this pigment is Rose Madder Lake.

Virgil’s Assessment:

Rose Madder NR 9 is not totally lightfast, but in my 16-years-in-my-window-facing-South test, it only faded slightly in mass/tone near the end of the 16 years (California sun through window glass,) which is much better than alizarin crimson. In a mixture with Winsor & Newton Flake White #1, it did fade somewhat in a more recent test, but no more than W&N’s (so-called) Permanent Alizarin.

Genuine rose madder lake (NR 9) faded less than PR 177, and much less than PR 83 in my 6-year sun test.

My understanding is that W&N moved their production facilities to China after a big corporate conglomerate bought the company. The madder-producing factory remained in England, but was recently shut down. So when their old stock of the Rose Madder Genuine runs out, there will be no more of it from Winsor & Newton.

Rublev’s Madder Lake is NR 9, and is just as transparent as alizarin crimson PR 83, and essentially the same hue, value, and chroma.

Michael Harding Paints also offer Rose Madder NR9. Here is his description: “a traditional Lake pigment, extracted from the common madder plant Rubia Tinctorum. As early as 1500 BC, this plant was grown in Asia and Egypt for the purpose of dying. The Egyptians are credited with developing several techniques to produce Lake pigments, the best of which came from plants 18 to 28 months old that had been grown in soil rich with lime and chalk. During the 17th century, red coats made for the British army were dyed with a shade of madder! Before you call me mad for putting such a terribly fugitive colour in the range, let me say in my defence that it’s included for its historic beauty and to help artists get closer to the pallets of earlier times. Unless you display it in direct sunshine, it will last for years with little change.”

Technical Links:

The Colour of Pigments Database: Rose Madder NR9: “Its Lightfast rating is II but most artists’ agree that the pigment is fugitive and the natural pigment is said to have even lower light fastness than synthetic Alizarin Crimson, which would make it very fugitive indeed. …It has held up in some old manuscripts & paintings, though.”

Pigment Through the Ages article on madder: “It’s a lake derived from the extract of the madder plant’s root (rubia tintorum) which the principal coloring substance is alizarin plus purpurin which is fading. It is one of the most stable natural pigments. It was in use by the ancient Egyptians for coloring textiles and then was continuously used until today. By the 13th century, madder was being cultivated on a fairly large scale in Europe, but there is no evidence of its use in medieval or Renaissance painting. Madder lake was most widely used in the 18th and 19th centuries, though never as extensively as the ruby-like lakes made from kermes, cochineal, brazilwood, and lac. Madder was formerly used in large quantities for dyeing textiles and is still the color for French military cloth. The cultivation of madder root almost ceased after a synthetic method for making alizarin was discovered by German chemists, Graebe and Liebermann, in 1868.

Venetian Red

Pigment Number: PR101

PR101 designates synthetic iron oxide pigment and depending on the manufacturing can be made in different shades and transparency. Venetian Red has been used as a name for PR101 for a long time.

The colors Virgil puts on his palette are determined by what he intends to paint but Venetian Red is a common one, especially for portraits.

One brand he uses is Michael Harding’s Venetian Red described as being semi-transparent and fast-drying with low oil content and low tinting power.

Technical Links:

A general note from a blog article “Venetian Red: Loved by Painters, Hated by American Colonists” by Julie Snyder: “Venetian Red is derived from natural earth clay tinted by iron oxide. The deep red pigment required by painters was mined for centuries from a quarry near Venice — hence the name. Interestingly, there still remains a pit outside Venice that is claimed to be the historical source for the finest of this pigment. The name Venetian Red, however, wasn’t coined until the 17th or 18th century. It has a superlative tinting power as it’s semi-opaque. Venetian red is a red pigment with a lower chroma (less bright) than other reds and it has a pinkish undertone, which can be seen when mixing it with white.”

From the Just Paint article: “Some Historical Pigments and Their Replacements” on Venetian Red: “Venetian Red, Sinopia, Venice Red, Turkey Red, Indian Red, Spanish Red, Pompeian Red, and Persian Red (or Persian Gulf Red, still considered the best grade for the natural pigment) are names used to describe locations where the natural red iron was extracted from the earth. Today, Red Iron Oxide is synthetically manufactured resulting in better consistency. Oxides have been used since pre-historic times and are still important pigments today. Venetian Red usually refers to a specific bluish hue of Red Oxide, but variations range from violet reds to yellowish ones.”

Alizarin Crimson

Pigment Number: PR83

Alizarin crimson PR 83 is a fade-prone pigment, rated ASTM Lightfastness IV, thus below the standard recognized as suitable for fine art purposes.

Sarah Sands, in a Just Paints article, summarizes the issue well: Sarah Sands wrote in a Just Paint e-newsletter from Golden Artist Colors, “If a single color embodies the dividing line between pigments considered suitable for permanent works of art and those that are suspect and poor in lightfastness, alizarin crimson (PR 83) would be it. And yet it is still used by many artists who are drawn to it in spite of its many problems. Some of that is driven by tradition, habit, and a sense of something special and unique about its color, a feeling that it exudes a natural earthiness and that more permanent substitutes can often appear too ‘clean,’ or too high chroma, to be a perfect replacement.”

Note that alizarin crimson PR 83 is not “the real thing,” but a synthetic substitute for rose madder, aka madder lake, NR 9. PR 83 was originally thought to be more lightfast than NR 9, but testing more recently has shown PR 83 to actually fade much worse and faster than NR 9.

Alternatives to PR83:

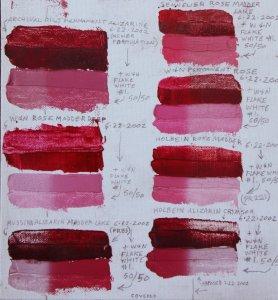

My own long-term sun exposure tests showed the least fading in M. Graham Quinacridone Rose (PV 19) and Archival Oils Permanent Alizarine (PR 122 and PR 175), and less satisfactory results with PR 177, which several companies are using as alizarin substitutes, some of which even have “permanent” in their names, which I regard as unwarranted based on my test results.

“The ones that performed best in my sun tests were Archival Oils Permanent Alizarine (which is a combination of PR 122 and PR 175,) and M. Graham’s Quinacridone Rose (PV 19.) Winsor & Newton’s Permanent Alizarin Crimson (PR 177) fared poorly in mixture with white, but interestingly, their Rose Madder Genuine and Rose Madder Deep (both NR 9, real rose madder lakes) took 15 or 16 years to show any fading in mass tone or glaze thickness, and in mixture with white faded no worse than W&N’s Permanent Alizarin Crimson PR 177. Their Rose Madder Deep is no longer being made, but the last information I have is that the Rose Madder Genuine is still available.

I would expect comparable performance from all the brands that use those pigments.”

Technical Links:

From the Just Paint article: “Some Historical Pigments and Their Replacements” on Alizaron Crimson: “Alizarin Crimson was created in 1868 by the German chemists, Grabe and Lieberman, as a more lightfast substitute to Genuine Rose Madder. This was accomplished by isolating part of the madder root colorant, 1,2 dihydroxyanthraquinone (Alizarin), from the more fugitive 1,2,4 trihydrozyanthraquinone (Purpurin). This is historically significant as it represents the first synthetic duplication of a pigment. Madder dates to before the time of the ancient Greeks. Pliny the Elder termed it “Rubia”, and it has been found in Egyptian tombs. Madder came to Europe during the time of the Crusades. The use of Genuine Madder practically ceased after the introduction of Alizarin. Lightfastness III, Alizarin Crimson was replaced 90 years later by the Lightfastness I Quinacridones, developed by Struve in 1958.”

Virgil’s lightfast tests for alizarin crimson and substitutes

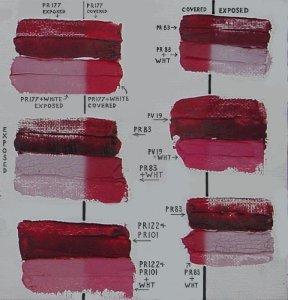

The images shown here are part of the test panels that sat in Virgil’s south-facing window for 6 years to see which of these paints would fade to what degree relative to one another. There was a strip of heavy black paper down the middle, protecting part of each sample from the sun, while the other end of each sample was exposed. Each paint was tested straight, spread thinly on top and thicker on the bottom for comparing the difference in performance in glaze thickness versus masstone, and then a second swatch of each paint mixed with Winsor & Newton’s Flake White #1 in a 50/50 mix was also applied. Compare the exposed side with the protected side of each swatch to see how much fading has occurred. PR 83 is alizarin crimson. PR 177 is at the upper left in the first image. In the second image, Alizarin crimson PR 83 results are shown in the bottom right side.

Vermilion and Cadmium Vermilion

Pigment Number: PR106, PR113

Virgil’s Assessment:

Virgil uses Vasari brand “Vasari Cadmium Vermilion Red Light”, which he describes as “somewhere between the hues of Dutch vermilion and Chinese vermilion; more red than orange. “

It is superior to genuine vermilion because it doesn’t seem to darken or change color in any way.

“I can only tell you what I’ve observed in my own tests. The real vermilions I tested began to show color change after a year or two in my south-facing window in California, and at four years they were noticeably darker and more grey-brown than red. At ten years, almost black. In normal indoor lighting, I’m reasonably sure it would take longer, but how much longer would vary depending on the light exposure.”

I’d expect real vermilion to behave the same way in egg tempera as it does in oils. Light exposure seems to be the cause, or a critical part of it, so whether or how long it would take for the color change to become noticeable would probably vary according to the amount of light it’s exposed to. It must be considered a gamble, as I see it, and an unnecessary one where another, more stable pigment is available.

I don’t recommend trying to grind vermilion. It’s a mercury compound and toxic, besides which it’s subject to changing its color from red to brown, then to a dark grey, then ultimately to black. There are better alternatives that do not do this.

Additional notes: In Virgil’s sun test panels, Cadmium Vermilion (PR 113) remained unchanged after 16 years in a window facing south in the California sun. The real vermilions (PR 106) that he tested began darkening noticeably after two years in that same window, and four years later were much darker, almost black, with very little red left in them. The cadmium reds (PR 108) also darkened slightly, which he found interesting and surprising. Only PR 113 remained unchanged. Granted that this was an extreme test, and as an accelerated-aging test, I don’t know how many years in normal lighting it would be indicative of, but what I found most significant about it was that PR 113 remained unchanged through the entire 16 years of daily sun exposure. This is why I have confidence in PR 113.

Technical Links:

The Color of Art Pigment Database: Red Pigments

From the Pigment Through the Ages page on vermilion: An orangish red pigment with excellent hiding power and good permanence. It’s a mercury sulfide mineral (cinnabar) used from antiquity through to the present though only scarcely due to its toxicity. Made artificially from the 8th century (vermilion), it was the principle red in painting until the manufacture of its synthetic equivalent, cadmium red.

A note about the original Vermillion (PR106). According to Gamblin’s Just Paint article on historical pigments and their replacements: “Vermilion is a toxic pigment made from Mercuric Sulfide. This naturally occurring ore is the source for Mercury, and was ground up as a pigment for centuries and termed Cinnibar or Zinnober. Early cultures of the Greeks, Romans and Chinese created Cinnibar artificially for centuries, as early as 6th century B.C., but it wasn’t until the 15th century that it was termed Vermilion. Direct sunlight causes it to darken substantially, and it was quickly replaced by the Cadmium Reds upon their arrival.”

The Winsor & Newton website has an article on the history of vermilion

Natural Pigments has an article on vermilion.

Mars Red

Pigment Number: PR101

Mars Red is synthetic iron oxide whose colours range from scarlet to maroon. It is known to be a permanent pigment with good tinting strength, good oil-drying properties, and poses no significant health hazards.

Virgil’s Assessment:

What some brands are calling Venetian Red is really Mars Red. Its tinting strength is much more powerful than the real Venetian red earth color.

Technical Links:

The Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online (CAMEO): Mars Red

Transparent Oxide Red

Pigment Number: PR101

PR101 comes in numerous shades under over a hundred marketing names. Some examples: Winsor & Newton’s Burnt Sienna, Venetian Red and Terra Rosa. Williamsburg’s Brown Pink is also PR101. Other names for synthetic iron oxide, PR101, are Transparent Red Oxide, Mars Red, Mars Violet, Caput Mortuum, English Red, and Persian Red.

For the most part, the different coloration is in the processing of the pigment. Pigments are crushed or mulled. They might be heated (baked or not) to produce different degrees of color. They might be processed with binders (oils) and formulated with fillers, driers or stabilizers which can effect their color and handling properties. The smooth or grainy textures will add various qualities to a color as well. In general, an organic earth pigment is mined, so the cost usually runs higher than a synthetic PR101. But higher-grade paints also use synthetics that lend variations to the tinting strength of PR101.

Virgil’s Assessment:

In the Facebook group, Virgil was asked for recommendations on brands of Transparent Oxide Red. His answer: Michael Harding, Gamblin, Rembrandt, Old Holland all have it, and Winsor & Newton has it but calls it Burnt Sienna. They’re all good, though Old Holland’s is thicker than the others, which is why I don’t use it much anymore.

The version of PR 101 that W&N have is actually transparent oxide red, which is a good pigment and very useful, but it’s more transparent and more orange than real burnt sienna.

A FaceBook member asked which transparent paints can be used to mix umber or sienna hues without sinking effects. Transparent Red Oxide PR102 (Synthetic PR101) is one of them.

Another reader asked Virgil to comment on a replacement for burnt umber using transparent oxide red and a small touch of phthalocyanine green. Virgil agreed it will be transparent and useful as a glazing mixture. It can be made more opaque and lighter in value to be more like burnt umber by adding a small amount of cadmium orange.

If you want dark, transparent browns, you can mix a whole range of them from transparent iron oxide red and phthalocyanine green in varying proportions. These will be darker in value and more transparent than burnt umber, and can take the place of asphaltum, Cassel earth, bitumen, mummy, and Van Dyck brown, all of which are problematic browns often used by various Old Masters.

Technical Links:

The Color of Art Pigment Database: Red Pigments