Topic List

General Comments

TBD

Indian Yellow

Pigment Number: NY20, PY110, PY139

Modern Indian Yellow is extremely variable when it comes to what pigments are used. Even within Lightfast rating of I, there is quite a difference with some fading much worse than others.

Virgil’s assessment: I have tested several brands’ Indian Yellows, and the only one among the ones I tested that didn’t fade was PY 110. The brand was Archival Oils. It would seem reasonable to expect other brands’ PY 110 Indian Yellows to perform similarly.

George O’Hanlon’s assessment: “Indian yellow was a pigment that was most likely derived from cow urine [cows that were fed mango leaves]. (There is no documented proof of the source but only a few literary references referring to this source. I had the distinct privilege to hold a ball of Indian yellow in my hands from the collection of Winsor&Newton and I must say it had the odor of urine, which is likely euxanthic acid.) The pigment was banned in the early 19th century due to the inhumane treatment of animals. Today, who knows what the color actually is since every paint manufacturer uses a mixture of pigments for this color. It is ludicrous to discuss its qualities since it depends on the pigments used by the individual artists paint manufacturer. It is useless to discuss color name, such as Indian yellow, when one is concerned about the actual pigment properties, such as lightfastness, permanence and compatibility.”

Technical Notes:

From the Just Paint article “Some Historical Pigments and Their Replacements”: “Also known as Puree, Peoli, or Gaugoli, True Indian Yellow (euxanthic acid) was produced by heating the urine of cattle fed mango leaves. The process was introduced to India by the Persians as early as the 15th century. Bengal, India was the chief exporter to Europe from the early 19th century until 1908. Local records indicate that the sale of Indian Yellow was prohibited as an act of preventing cruelty to animals, as mango leaves do not have the proper nutrients for cattle.”

Chemistry World Article, “The Hunt for Indian Yellow”, on the history of the pigment: “The origins of Indian yellow, which first appeared in the 14th century and then vanished at the end of the Victorian era, are as mysterious as Mona Lisa’s smile. A popular legend places the pigment’s source as the Bihar province of India, made from the urine of Bihari cows fed only mango leaves; solids were then gathered from the concentrate and left to bake in the sun, eventually turning into the intense pigment so valued by artists. The story continues that Indian yellow was banned in the early 1900s over concerns of animal cruelty. This tale explains the mysterious emergence and sudden disappearance of this astonishing colour, but is largely unsupported with evidence and disputed by modern researchers. To this day, the truth about the dye remains unknown.”

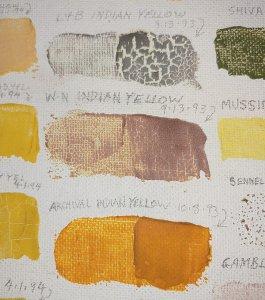

Lightfast Tests with Indian Yellow (14 years)

The Middle swatch is Winsor & Newton’s Indian Yellow, after 14 years in my south-facing window. It started out being the same color as the sample below it, Archive Oils Indian Yellow (PY74 + PR101). The Archive Oils brand is the only Indian yellow that Virgil recommends.

Mars Yellow

Pigment Number: PY42

Virgil’s assessment:

Mars Yellow is made from synthetic iron oxide (PY 42).

Virgil uses Mars Yellow as an alternative to Yellow Ochre. He includes it in his portrait palette.

“Michael Harding’s Yellow Ochre is actually Mars yellow, by the way. I think Williamsburg, Vasari, Gamblin, Rembrandt, and Langridge all have Mars yellow oil paints, if I’m not mistaken. Rublev has a transparent version of yellow iron oxide, recently added to their line.”

The problem with Yellow Ochre? “The only issue is its clay content, which subjects it to expansion and contraction in reaction to changes in relative humidity. This is a factor in the cracking of oil paintings on stretched canvas, but not so much on rigid panels or canvas glued to panel. Mars yellow is a good substitute for yellow ochre if one can handle its higher tinting strength. Both are of the utmost lightfastness.”

“Umbers and ochres contain clay, which is hygroscopic and undergoes shrinking and swelling due to changes in relative humidity. Synthetic iron oxide (Mars) pigments are more stable in that regard, are lightfast and high in tinting strength. That being said, natural earth pigments have a long record of good performance, and are as lightfast as the Mars colors, which is to say, more lightfast than anything else.”

More about synthetic iron oxides pigments: they are like natural earth pigments, but “are manufactured rather than mined from the ground, so there is no clay in them. They are the same range of colors, but their tinting strength is much higher than the natural earth colors. They are as lightfast as the natural earth colors, which is to say they are more lightfast than any other colors, as are the ochres, siennas and umbers, which never fade.”

Synthetic yellow ochre, Mars yellow, have been made since the early 1920s.

Technical Link: The Color of Art Pigment Database: Yellow Pigments: PY42

Note: color, transparency and oil absorption can vary widely between brands, due to manufacturing variables, iron oxide (red) to hydrated iron oxide (yellow) ratios, particle size, impurities, additives, and fillers.

Lead Tin Yellow

Pigment Number: none, not listed

Virgil’s assessment: [Included in his portrait palette.]

Lead-tin yellow is lead stannate or lead ortho stannate, which ceased to be available on the pigment market long ago, and only recently was reintroduced by small companies like Robert Doak and Natural pigments. Before that, I was buying lead stannate powder from a chemical supply company and mulling it into paint myself, as the only living artist using lead-tin yellow at that time (1980s and ’90s). It hasn’t been assigned a pigment number because it’s not being marketed as a pigment except by the small companies I mentioned, which are below the radar of the pigment industry.

Lead tin yellows vary from pale yellow inclining slightly toward green to somewhat darker inclining toward orange, depending primarily on how much heat the pigment is subjected to. Heat makes it darker and redder. Its chroma is lower than cadmium or chrome yellows.

Dries fast.

Technical Link: The Color of Art Pigment Database, Yellow Pigments Click here

Cadmium Yellow

Pigment Number: PY35

Virgil’s assessment:

On his palette: Rublev’s Cadmium Yellow and Cadmium Yellow Light.

Cadmium yellows today vary in their long-term performance if my 16-years-in-the-window sun test is any indication. Some held up very well, some crumbled, some cracked, and some stayed sticky for ten years, collecting dirt the whole time. None of them changed color, though. In Van Gogh’s time, methods of improving the pigment had not yet been developed. I can tell you that Winsor & Newton’s cadmium yellows (which are available in Quito) fared better than most of the others in my test. The one that stayed sticky for ten years was Mussini, and one of the ones that crumbled was Old Holland.

Cadmium yellow is a good substitute for chrome yellow.

Technical Link:

The Color of Art Pigment Database, Yellow Pigments

Chrome Yellow

Pigment Number: PY34

Chrome yellow is included in Virgil’s portrait palette. Compared to cadmium yellow, chrome yellow makes dense, opaque paints that brush out long and flowing, yet the brush marks hold their shape. It offers greater opacity and tinting strength.

Chrome yellow was introduced in the early 19th century as a relatively inexpensive, bright, and opaque yellow. But it was not lightfast: it tended to darken on exposure to light. It was replaced by cadmium yellow, a more stable, opaque pigment. Mid-20th-century modifications to the original form of the pigment now make it lightfast and resistant to change.

The Natural Pigments website has a page dedicated to Chrome Yellow. Rublev Colours offers three different chrome yellows: Chrome Yellow Primrose, Chrome Yellow Light and Chrome Yellow Medium. According to Natural Pigments: “Lead chromates dry moderately well, although chrome yellow primrose dries slower than the light and medium varieties. It is known that they enhance the film-forming qualities of oil paints.”

Technical Links:

See the Color of Art Pigment Database: Yellow Pigments

Read more about chrome yellow on the Pigments Through the Ages Website.

Naples Yellow

Pigment Number: PY53 (PY41 for Genuine Naples Yellow)

Vasari Naples Yellow Genuine is very high-chroma, almost as high as cadmium yellow. Michael Harding’s is almost as high in chroma as Vasari’s. Both are lead antimoniate, lightfast, and expensive.

The genuine naples yellow pigment is very rare, so few companies offer PY41. You will only find the genuine pigment in Rublev Colours and Michael Harding artists oil colors. There may be one other line, but Williamsburg is not one.

Dries very fast

Jaap Boon, conservation scientist, provided information about Naples yellow that bears consideration as well. He says it is easily destroyed by solvents normally used in restoration procedures. Whether this also applies to lead-tin yellow is unclear. I’ll need to query him about that.

Technical Links:

From JustPaint.org article: Also known as Antimony Yellow and Juane Brilliant, Naples Yellow is a lead-based pigment made from Lead Antimoniate. It was produced as early as the 15th century, although it is said to have been found on tiles of ancient Babylonia. The first known formulae date from 1758.

Yellow Ochre

Pigment Number: PY43

On his palette, Virgil has replaced yellow ochre with Mars yellow, due to concerns over the clay content, which causes shrinking and swelling with changes in relative humidity.

The problem with Yellow Ochre? “The only issue is its clay content, which subjects it to expansion and contraction in reaction to changes in relative humidity. This is a factor in the cracking of oil paintings on stretched canvas, but not so much on rigid panels or canvas glued to panel.

The oldest yellow pigment is yellow ochre, which was amongst the first pigments used by humans.

Inorganic, dries very fast.

Ochres vary widely in transparency; some are quite opaque, while others are valued for their use as glazes.